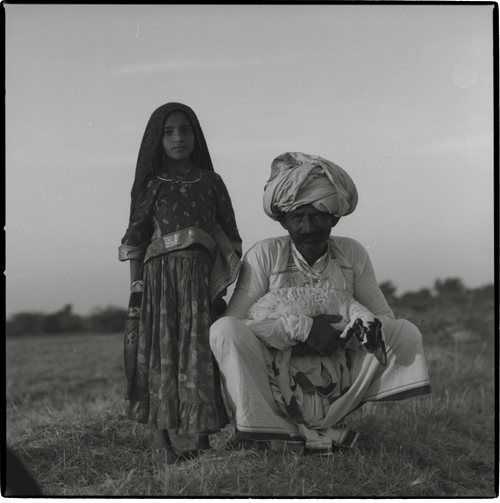

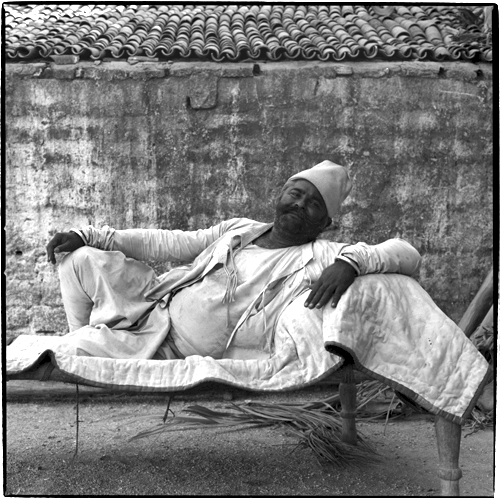

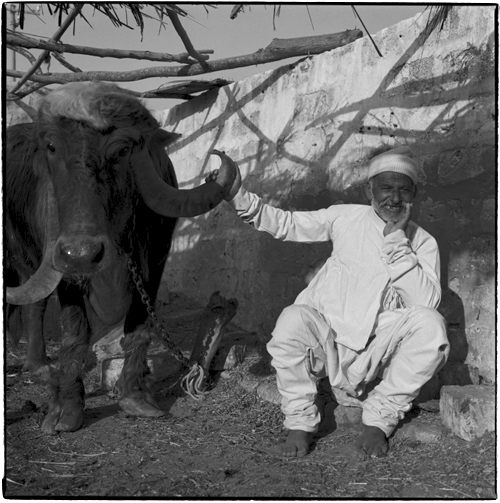

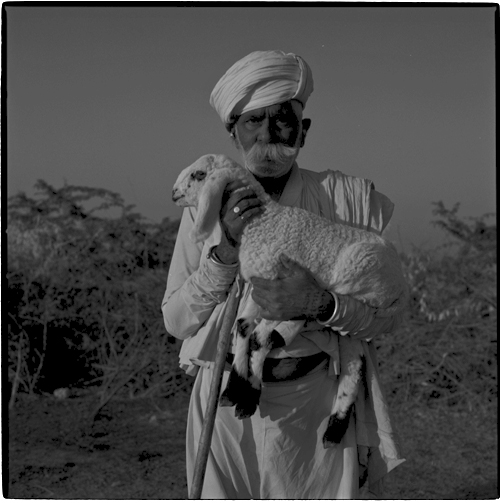

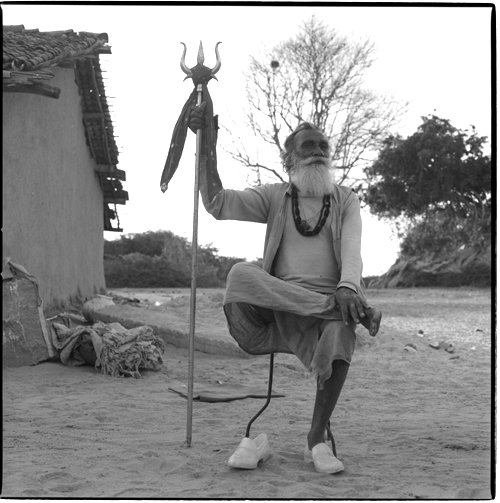

In the days of 120 film and a life without children I asked Ilford to sponsor me on a trip to the wilderness of Gujarat to photograph Saints & Nomads.

I set off with an old Hasselblad and some reflectors and absolutely no idea as to how I would find the aforementioned heroes of life in the wilds of India.

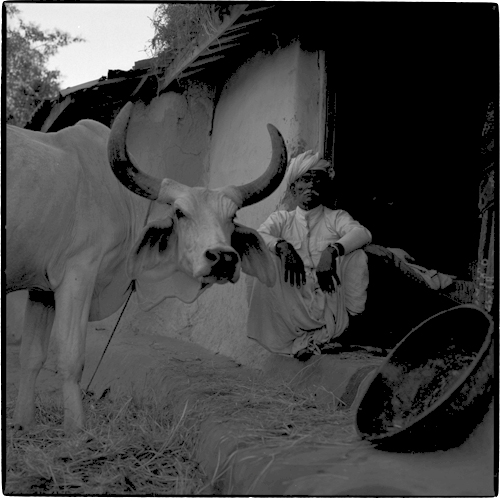

Through the travel grapevine I heard of a camp in the Raan of Kutch with mud huts and wild asses. This was my first stop. Appearing out of nowhere with mad ambitions and a crazy vision of life plus a personal vow never to photograph anyone without their express consent, I met with the Prince of the area.

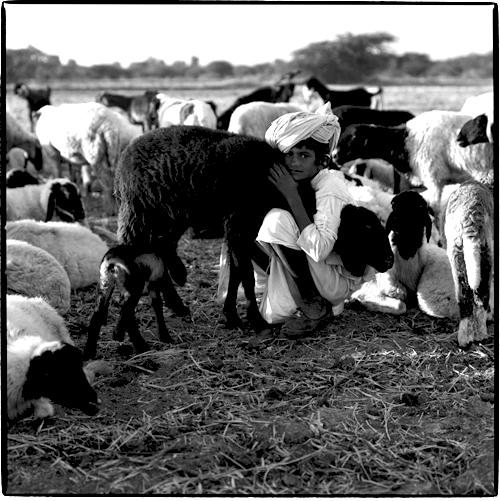

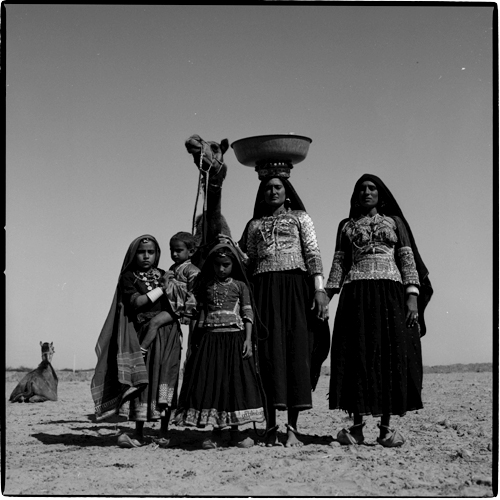

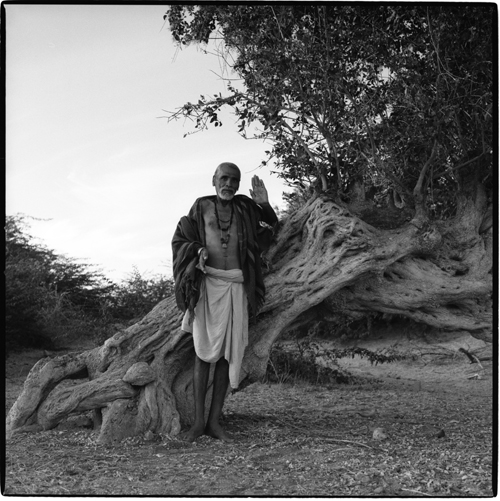

I had landed in an ancient land. His father controlled several thousand farmers and nomadic tribes and he was bored, he was intrigued. He pulled together a team of shepherds and some servants, loaded charpoys and mung beans onto a jeep and we headed off into the wild hinterlands of the furthest western deserts of India.

We travelled for days at a time, sleeping in fields, drinking camels milk tea made by Jat women on camel dung fires, slept, surrounded one night by 10,000 sheep with a ring of shepherd protecting the flock and us, all night, by calling to one another to protect us all against dacoits, and entertained nomadic travellers around our camp fires at night.

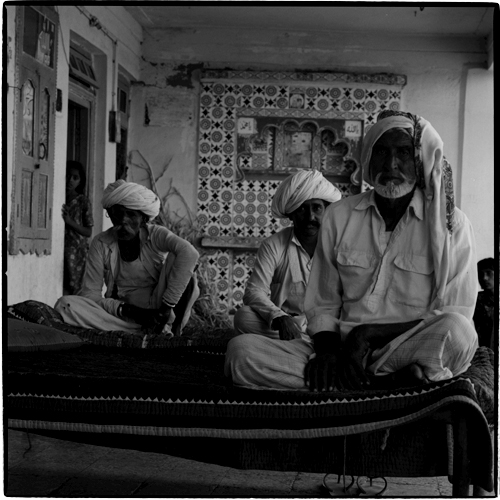

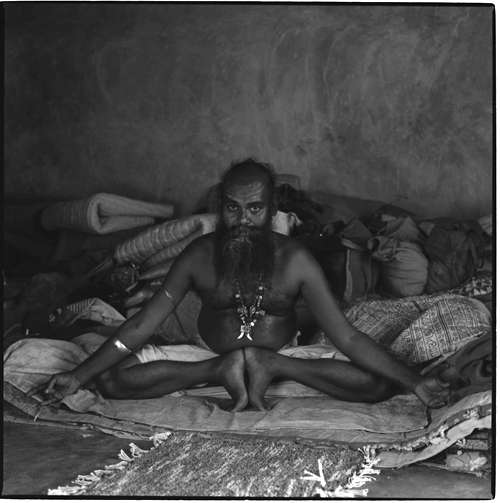

I bargained with men, sadhus and women for the right to photograph these people, almost all of whom had never seen a white person. I sat in circles of elders in villages whilst they discussed me, my hair colour, my skin, my height, and whether it was ok to have me make portraits. They joy was that each time these discussions needed many hours so the villagers were bored, had lost interest in me, had moved on. And the greatest joy with the Hasselblad was that I could engage with and talk to my sitters yet when I looked down into the camera there was no real understanding that that was the moment of the image being taken, so nothing clouded the simplicity of the interaction.

My sex gave me privilege. It was most unexpected. Men allowed me to photograph them and their women because they felt they could dominate me, should they need to. My guards and protectors were from their local tribes and spoke kindly of me. Polaroids smoothed tense moments and I built up, over many months of travel, a unique catalogue of portraits of men and women in the Land that Time Forgot.

[ezcol_1half]

[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]

[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]

[/ezcol_1half_end]

[/ezcol_1half_end]